Rushdie's Akbar isn't so great

In the day's last light the glowing lake below the palace-city looked like a sea of molten gold. A traveller coming this way at sunset -- this traveller, coming this way, now, along the lakeshore road-might believe himself to be approaching the throne of a monarch so fabulously wealthy that he could allow a portion of his treasure to be poured into a giant hollow in the earth to dazzle and awe his guests. And as big as the lake of gold was, it must only be a drop drawn from the sea of the larger fortune..."

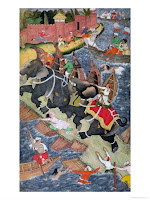

Thus begins Salman Rushdie's tenth novel, The Enchantress of Florence (Random House), with the arrival of Mogor dell'Amore (Mughal of Love) at Fatehpur Sikri, the red sandstone capital city of Emperor Akbar. Mogor dell'Amore is carrying with him a secret so startling that, once told to the emperor, it will force another secret to come tumbling out of the royal family's musty cupboards stuffed with nasty tales of gore and lofty stories of Mughal glory, forcing Akbar to order the redrawing of his genealogical tree by the palace artist, a brooding man given to dark thoughts.

Rushdie has tried to recreate life in two cities separated by land and sea. There's Fatehpur Sikri, where Akbar agonised over faith, fidelity and filial loyalty -- when and how would Salim, remarkably cruel as a young boy, turn on him? -- while unbridled hedonism prevailed in the bed chambers of princes, princesses and others less privileged. Then there's Niccolo Machiavelli's Florence where seductive mistresses cast magical spells -- tulips painted on underclothes -- and authority is exercised through appalling torture even as humanist philosophy sprouts from its violence scorched soil. What is common to both places is the brutality of power.

Mogor dell'Amore, with his distinctive European features and yellow hair, gets to tell his secret to Akbar after demonstrating his 'magical powers': He is the son of a Mughal princess, the forgotten youngest half-sister (the Mughal court, let's not forget, till it lasted, was teeming with half-siblings, each conspiring against the other) of Babar, the grandfather of Akbar. How Qara Koz (Lady Black Eyes) becomes the mistress of Argalia, a Florentine soldier of fortune, and the rest of the tale is told in the manner of The Thousand and One Nights. But Rushdie, for all his efforts to create magic through words -- "His hair was long and black as evil and his lips were full and red as blood"; "It was as if every man in the city had turned werewolf and was howling at the moon"; "So it was that Shah Ismail of Persia drowned in the 17-year-old princess's black eyes"; "She unleashed the beauty she had kept veiled and he was lost" -- fails to take his readers (or at least this reader) on a magical mystery tour. His first historical novel, woven around romance and fantasy, heavily researched (as the detailed bibliography shows) and strenuously crafted, does not quite add weight to his admirable repertoire of fiction. Rushdie began to slip with The Moor's Last Sigh, and hasn't quite stopped sliding down the hill since then. His ethereal Jodha Bai, who satiated the mortal Akbar's desire by scratching him -- "she was adept at the seven types of unguiculation, which is to say the art of using the nails to enhance the act of love" -- is a pathetic parody of history. Was there ever a Jodha Bai in Akbar's palace? "She existed," writes Rushdie, "She was immortal, because she had been created by love."

To his credit, though, Rushdie stops short of venerating Akbar, and mocks at those who refer to him as 'Akbar the Great', for that would be tautology and utterly silly. And when Akbar would say, "Allah-o-Akbar", as he did before chopping off the "unnecessary head" of a "pompous little twerp", the Rana of Cooch Naheen (that's what Hindu rulers, including in brave Rajputana where tales of valour outnumber the grains of the desert's sand, had allowed themselves to be reduced to under Mughal tutelage) did he mean "God is Great" or "God is Akbar"? That's a question nobody would dare ask, for secular myth-making has placed a glowing halo around the head of Akbar, who in real life was as great and merciful as his god but of which little is mentioned in our history books.

In an interview to Reuters, Rushdie said writing The Enchantress of Florence "saved him from the wreckage of his divorce last year from fourth wife Padma Lakshmi". By spinning a yarn from palace intrigue and bedroom politics, by taking refuge in magical realism, he managed to escape the real world which, at that moment, had turned cold to him. "It was a good place to go at a time when my private life was in a state of wreckage, and yes it was, I suppose, a bit of a refuge," Rushdie told Reuters. "I think in the end what got me through it was the long familiarity of the necessary discipline of writing a novel. I found that in the end a lifetime's habit of just going to my desk and doing a day's work and not allowing myself not to do it is what got me back on track. I was derailed for a while. I was in bad shape and it brought me back to myself," the writer explained.

While that cathartic experience may have helped him survive a personal crisis, it has not really produced a book that's worth comparing to his early novels. But then, it does provide a glimpse of what life may have been like within the walls of Akbar's city where charlatans and philanderers, flatterers and chatterers, connived and plotted as a Mughal megalomaniac, not quite sure of his faith as also that of others -- "In the melancholy after battle, as evening fell upon the empty dead, below the broken fortress melting into blood, within earshot of a little waterfall's nightingale song... the emperor in his brocade tent sipped watered wine and lamented his gory genealogy... He was not only a barbarian philosopher and a crybaby killer, but an egotist addicted to obsequuiousness and sycophancy... He felt burdened by the names of the marauders past, the names from which his name descended in cascades of human blood", presided over the destiny of Hindustan. As for life in Florence, we will leave that for another day.

Coffee Break / Sunday Pioneer / April 27, 2008.

No comments:

Post a Comment